This post is in reply to psychologist William A. Zingrone, who recently wrote a thoughtful and challenging review of my book, The Illusion of God’s Presence: The Biological Origins of Spiritual Longing. The scientific issues he raised deserve serious discussion, and because he and I are now Facebook friends, it seemed natural to write this in the style of an open letter.

Dear William,

Thank you for your kind review, which shows evidence of a careful reading. As you noted, we agree on nearly all of the important issues: that religions are false, that they do more harm than good, and that science brings a light that dispels religious darkness. I suspect we agree on much more, like issues of separation of church and state, women’s rights, and the need for better teaching of science and critical thinking in our public schools. But here I want to discuss our few differences, which mainly involve choice of words or scientific controversies. Even on these few points of contention, I suspect we agree more than your review suggests. I think if we both try to see these issues in their full subtlety and shades of gray, much of our apparent disagreement will fade away. In any case, I’m grateful for your criticisms because they’ve made me consider some of these ideas in a new light.

Why “Illusion” Is the Right Word

You argue that “delusion” is a better word than “illusion” to describe the feeling of God’s presence because an illusion is something intrinsic to the brain and accessible to all people, whereas not all people feel god’s presence. You write,

An illusion is part and parcel to our innate perceptual interpretation system. It is universal and all humans experience them, they are inescapable. Not all humans however, fall sway to the god delusion, as Richard Dawkins correctly termed it in the title of his famous book. Wathey purposely contrasts his title to Dawkins’s, describing the feeling of the presence of god as an illusion, which I will argue is an obvious mistake.

I agree that the word “illusion” is often misused. Eastern and New Age mystics tell us (incorrectly, in my view) that some ill-defined Universal Consciousness is all that is truly real and that all of what we perceive as physical reality is an illusion. Some neuroscientists, like David Eagleman, say much the same, not because they believe in Universal Consciousness, but because perception is a neural construct — a computationally synthesized and imperfect model of external reality, not reality itself. On this last point I take the view of psychologist Richard Gregory: to call all of perception an “illusion” renders the word meaningless. Gregory chose instead to use “illusion” only for those peculiar situations in which the brain’s internal model of reality differs from it so much that we grossly misperceive what is really there. This is the sense in which I am using the word in my book, both for sensory illusions like the Ames room and for the feeling of God’s presence.

After defining “illusion” and “delusion” and offering a lucid explanation of cognitive impenetrability, you write,

Visual and other perceptual illusions are truly cognitively impenetrable. They are part and parcel of our perceptual system’s processing of information. We can’t ignore them or make them go away. Furthermore, all humans experience them, as they are hard-wired into our brains. They are universal.

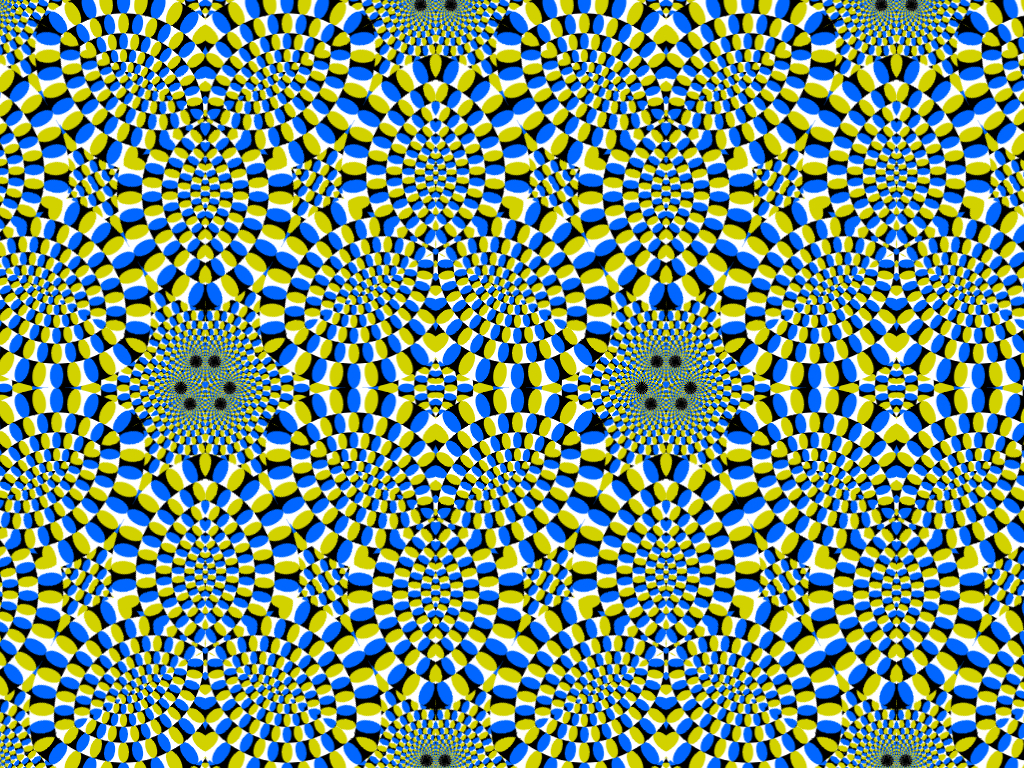

This is mostly true for most sensory illusions, but there are noteworthy exceptions. Not everyone sees the same illusory colors in the Benham’s disk illusion. Individuals differ significantly in their ability to perceive Mooney faces — impoverished images of faces in which the illusion is that there is no face present, when in reality there is. This variation among individuals was evident in the audience at my talk in Los Angeles, and it was one of Craig Mooney’s consistent findings in his original papers. Interestingly, there is a significant effect of learning in the Mooney face illusion, as children get better at perceiving the faces from ages 7 to 13. Similarly, there is significant individual variation at perceiving the anomalous motion illusions of Akiyoshi Kitaoka. There’s a stark difference on this even between my wife and me: I see the motion vividly; she doesn’t see it at all. This means that her brain’s internal model of reality is better — more closely matched to reality — than mine, at least when we’re looking at these illusions.

So I take issue with your characterization of illusions as universal, but that’s not the main point I want to make here. My main point — and the reason the illusion of a divine presence is so hard to produce on demand in oneself or someone else — is that it is not an illusion that happens in low-level sensory cortex. This was the point I tried to make in the talk and in the book, but maybe I didn’t emphasize it enough in the book. My hypothesis is that the illusion originates from a neural model of reality in high-level association cortex (mainly the temporoparietal junction and orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex), parts of the brain that are concerned with human social behavior, selective attention, embodiment, and reinforcement learning. High-level models of this kind are not as easily fooled by sensory trickery. There is no simple sound you can play or image you can show to someone and thereby reliably and consistently make them feel God’s presence. But that doesn’t mean it’s not an illusion when someone does have that feeling. It only means that their neural model of reality that expects a loving presence, in some particular context of emotion and mood, is not accurately modeling reality, and this is the definition of illusion for folks like Richard Gregory and me.

The essence of my idea is that the neural model that is expecting a loving presence does accurately model reality in early infancy, and this is mainly what it’s for — the innate foundation of mother-infant attachment. As you correctly point out, attachment is largely a function of learning during the early years of child development, but, like face perception, it is a highly specialized kind of learning that requires a foundation of innate knowledge. I emphasized this point in the talk and in several places in the book. From chapter 6:

This might seem at first to be a question of nature versus nurture: is the source of religious feeling and behavior innate or learned? As I tried to explain in chapter 3, however, nearly all behaviors of any great complexity are to some extent both innate and learned. The interesting questions concern how genetic and environmental factors contribute to individual differences in the behavior, and how those contributions come into play throughout infancy, childhood, and later life.

And from chapter 13:

We are learning machines, but our capacity to learn is neither boundless nor aimless. Our evolutionary history has shaped our brains such that we know some essential things at birth — what tastes good, smells good, feels good — and the most important of these things, I suggest, is that another being exists, one who brings love and comfort. This innate knowledge persists into adulthood as the foundation of our social nature — the direction in which evolution has aimed our learning.

Also, it is not entirely true that the illusion of a sensed presence cannot be experimentally evoked. In my talk I freely admitted that there was no image I could put up on the screen that could make people in the audience feel God’s presence. I then made the point about the illusion occurring in high-level association cortex and speculated that, if I had some magical way to manipulate another person’s mood, emotion, motivation, expectation, and sensory input in just the right way, I might be able to conjure the illusion of a divine presence for that person. Yet even without recourse to magic, a few obscure experiments of this kind have been tried.

I discuss one of them, done by psychologist James Leuba in the early 20th century, in my forthcoming book. Each of Leuba’s subjects sat blindfolded for ten minutes in a large, quiet, dimly-lit room. Several experimental assistants sat behind the subject, twenty-five feet away. The subject was told that one of the assistants might come and stand near him, behind the chair. He was asked to “assume an attitude of passive expectancy” and to raise a hand whenever he became aware of a presence. At irregular intervals an assistant would silently approach the subject, stand behind him for a few seconds, and then withdraw. The room had a thick rug, so the subjects detected only about half of these approaches. Occasionally an assistant would deliberately make subtle sounds as if preparing to approach the subject, but then not do so. After each session the subject gave a detailed account of the experience.

About half of the subjects reported perceiving not only the assistant — by sound or movement of air — but also — at other times, and without sensory cues — a qualitatively different sense of presence. At least some of these occurred with no one near the subject and often involved strong emotion — fear in some cases — and a highly specific feeling of spatial localization of the presence or of being surrounded by it. In summarizing the results, Leuba emphasized not only the intense emotionality often associated with the sense of presence, but also the attendant feeling of certainty that he called “intensity of assurance”:

With very rare exceptions our subjects found no difficulty in separating the inference of a presence, made on the basis of perceived sounds, from what they called a Sense of Presence. An inferred presence left our subjects more or less indifferent, while the Sense of Presence involved emotions varied in character and usually intense, and it carried with it also an intensity of assurance lacking in the mere inference. It must be emphasized that, however convincing the experience, the nature of the Presence remained extremely vague.

From page 286 of: Leuba JH (1925) The Psychology of Religious Mysticism. Harcourt, Brace: New York

The study used only seven subjects and so carries little statistical weight. It shows, however, that a compelling illusion of a sensed presence can be elicited merely by suggestion, isolation, and partial sensory deprivation. Of course the illusions described by Leuba’s subjects are only fragments of the illusion of God’s presence described by most religious believers. As such they are similar to the illusory sensed presences that can be elicited by direct electrical stimulation of the temporoparietal junction in neurological patients.

My main point here is that the illusion of God’s presence lies at one end of a spectrum of illusions characterized by hierarchical location in the brain and by ease of elicitation. At one end are the familiar and easily elicited sensory illusions — like the Ames room — that result from neural models in relatively low-level sensory cortex. At the other end are complex illusions of emotion, mood, motivation, expectation, embodiment, and interpersonal relations — like the illusion of God’s presence — that result from neural models in high-level association cortex. Nearby on this spectrum are the vague and not especially religious sensed presence illusions — like those described by Leuba’s subjects, mountaineers, polar explorers, and some neurological patients. Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum are subtle multimodal sensory illusions of embodiment that can only be elicited with elaborate stimuli carefully synchronized across two or more sensory modalities. Examples include the rubber hand illusion and the virtual reality out-of-body experience. And somewhere between these and the Ames room lie the visual illusions that not all people see in a consistent way, like Benham’s disk and Kitaoka’s anomalous motion illusions. These involve neural models at the confluence of visual submodalities like color and motion. What all of these illusions have in common, across the entire spectrum, is a misperception of some specific aspect of reality caused by a shortcoming in our neural model of that aspect, and that is why I think the word “illusion” is appropriate for all of them.

Why “Delusion” Is the Wrong Word

By far the main reason I dislike “delusion” as a descriptor of the feeling of God’s presence is that “illusion” is so much better — more scientifically precise and accurate — for the reasons I just laid out. To call the experience an illusion puts it where I think it reasonably belongs: in that spectrum of misapprehensions of reality that come from nonpathological deficiencies in neural models of reality. I admit there is a gray area where the two concepts overlap. Also, the word “delusion” is commonly used in at least two distinct ways: (1) as “a false belief or opinion” — one of four definitions in my big fat Webster’s dictionary, and (2) as psychiatrists define it in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

In common parlance, however, most people seem to take “delusion” to imply psychopathology, whether or not they are familiar with the DSM or the four definitions in my dictionary. We most often encounter the word in phrases like “delusions of grandeur” or “paranoid delusions,” and our new president has only nurtured such usage in the mainstream press. Even the online definition you cited clearly identifies it as a pathology:

From the wiki: “A delusion is a belief that is held with strong conviction despite superior evidence to the contrary. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, or other effects of perception.”

Why confuse the issue by suggesting psychopathology for something (religion) that we both agree is not specifically and consistently tied to mental illness?

I gather from your review that one reason you favor “delusion” concerns its presumed origin through learning. You write,

The “God Delusion” as Dawkins correctly termed it, can be discarded, or for so many is never succumbed to regardless of formidable and coercive religious upbringing. In addition, when children are raised secular without any religion, they don’t look to fill any god-shaped hole in their heart, not yearning for some transcendent caregiver. That idea, that delusion, has to be taught, and it doesn’t always take.

Elsewhere you distinguish it from illusions, which you contend are “hard-wired into our brains” and “universal” to all people. I already discussed illusions that are not universally experienced. But I don’t find this distinction — that illusions are innate and delusions are learned — in any generally accepted definitions of the words. I see no evidence to support it, and I see considerable evidence against it. Earlier I noted the effect of long-term learning on face perception and the Mooney face illusions, and short-term learning appears to be important in illusions of embodiment, like the rubber hand illusion. Conversely, schizophrenia — a major cause of delusions of grandeur, persecution, mind control, alien implants, and hearing God’s voice — is highly heritable. So is narcissistic personality disorder, the psychopathology that appears to have spawned our president’s delusions and propelled him to electoral success.

Maybe you meant that only religious delusions must be learned — not the ones we associate with mental illness — but I see problems with that idea, too.

Why Indoctrination Alone Cannot Account for Religious Belief

Throughout your review you assert that religion is entirely a product of culture, learning, and indoctrination. Here’s one such passage:

I contend that without direct religious indoctrination or exposure to our cultural assumptions of a religious nature that “there must be something, somebody out there” most people will not undergo a feeling of god’s presence. It is a delusion that must be taught, not an unchangeable biologically oriented illusion.

You’re not the first person to criticize my book on these grounds. The first was an editor who wrote one of the many rejection letters I collected from major publishers. But if this assertion were true, then, on average, pairs of identical twins (who have 100 percent of their genes in common) should be no more alike in their religiousness than are pairs of fraternal twins (who share only about 50% of their genes).

But that’s not what we see when we do twin studies of adult religiousness. Instead, pairs of identical twins are significantly more alike in their religiousness than are pairs of fraternal twins, enough to indicate that about 40 to 50 percent of the variance in religiousness across individuals comes from genetic factors. This is compelling evidence that religion is partly a biological thing, somehow a product of evolution. It remains an open question as to whether religion was itself adaptive in our prehistoric ancestors or was instead merely a by-product of some other adaptation, but the twin studies compel us to accept that something about human religiousness has been shaped by the forces of natural selection. Religion cannot be entirely a product of indoctrination.

In support of your argument to the contrary, you write:

I note also that many of us raised in a faith, whether lightly encouraged and not at all coerced, or fully compelled to believe and smothered within the Xian cocoon as so many have experienced, can readily walk away from such indoctrination, including the fleeting feeling (if one ever experiences it) of god’s presence. It does not seem at all to be a biological imperative along the lines of chick imprinting, an analogy Wathey draws from the study of ethology, or to be an unconscious urge left over from our infancy for a Freudian-like “mother model” as he also maintains.

Yes, religious people can learn to see the illusion for what it is and walk away from it, but that in no way contradicts the findings of the twin studies. If about half of the variance in religiousness comes from genetic factors, then the other half doesn’t, and it is in that other half — the environmental factors — that we apostates find our escape from the heritable aspects of human nature that make us prone to religiousness. And remember, those genetic factors vary throughout the population; it’s that variance that the twin studies detect. Some individuals are therefore heritably, genetically less likely than average to become religious, all else being equal. For them, walking away from a religious upbringing is relatively more likely. Some of this is evidently sex-linked, as apostasy is more likely in men than in women.

You mention the religiousness of Francis Collins, distinguished director of the National Institutes of Health, as an example of the role of indoctrination and culture in religious belief:

Children in the more conservative sects of many religions are taught that they should be able to experience god; feel the presence of god as part of their daily life. Without this instruction, few people come to this delusion on their own. Interpretation of transcendence is dictated by culture: Francis Collins saw the Trinity, not Allah in the waterfall.

Yes, Collins admits that the sight of a tripartite frozen waterfall helped push him over the edge when he took his leap of faith into Christianity, and it was a culturally transmitted piece of Christian doctrine that shaped his interpretation of that experience. But there is much more than that to the puzzle of Francis Collins and others like him, and I believe the full story supports my case in a profound way.

You are right to emphasize the importance of learning, indoctrination, social pressure, and other cultural forces in the maintenance and propagation of religion. After all, the transmission of religious denomination from parent to child is primarily cultural. Nowhere in my book do I deny this. But this cannot be the whole story. It does not explain why religion is a cultural universal, why religiousness is significantly heritable, why women are more religious than men, why religion is obsessed with sex, why God is so often seen as not only cruel and judgmental but also unconditionally loving, and why the infantile aspects of religion — like prayers of supplication to a divine savior — often creep back into religions, like Theravada Buddhism, that declare these aspects theologically incorrect. And nowhere is the failure of a purely cultural explanation of religion more evident than in the puzzling religiousness of a small but significant minority of elite scientists.

The Puzzle of Elite Religious Scientists

Neil deGrasse Tyson called our attention to this puzzle in a lecture he gave at the Salk Institute in 2006. He cited data from a paper in Nature that examined the religious beliefs of our most elite scientists, members of the National Academy of Sciences. The point of the paper was that about 93 percent of them reject belief in a personal god who answers prayer, but Neil argued that the authors had missed the most important and puzzling thing in their data: Why do 7 percent of them believe in God? Why is that 7 percent not zero? These are some of the most brilliant and accomplished scientists in the world. You cannot argue that they need more training in critical thinking skills, evolutionary theory, empiricism, or the scientific method. If indoctrination is the sole source of religion, as you insist, then the best you can do in the face of these data is to argue that these elite religious scientists must have received extraordinarily intense religious indoctrination, and their scientific training was somehow insufficient to overcome it.

The facts, however, do not bear this out. Francis Collins is one of those mysterious seven percent. Of his upbringing he writes,

My early life was unconventional in many ways, but as the son of freethinkers, I had an upbringing that was quite conventionally modern in its attitude toward faith — it just wasn’t very important.

…

I was vaguely aware of the concept of God, but my own interactions with Him were limited to occasional childish moments of bargaining about something that I really wanted Him to do for me. For instance, I remember making a contract with God (at about age nine) that if He would prevent the rainout of a Saturday night theater performance and music party that I was particularly excited about, then I would promise never to smoke cigarettes. Sure enough, the rains held off, and I never took up the habit. Earlier, when I was five, my parents decided to send me and my next oldest brother to become members of the boys choir at the local Episcopal church. They made it clear that it would be a great way to learn music, but that the theology should not be taken too seriously. I followed those instructions, learning the glories of harmony and counterpoint but letting the theological concepts being preached from the pulpit wash over me without leaving any discernible residue.

…

Graduating [high school] at sixteen, I went on to the University of Virginia, determined to major in chemistry and pursue a scientific career. Like most college freshmen, I found this new environment invigorating, with so many ideas bouncing off the classroom walls and in the dorm rooms late at night. Some of those questions invariably turned to the existence of God. In my early teens I had had occasional moments of the experience of longing for something outside myself, often associated with the beauty of nature or a particularly profound musical experience. Nevertheless, my sense of the spiritual was very undeveloped and easily challenged by the one or two aggressive atheists one finds in almost every college dormitory. By a few months into my college career, I became convinced that while many religious faiths had inspired interesting traditions of art and culture, they held no foundational truth.

From chapter 1 of: Collins FS (2006) The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. Free Press: New York

This does not sound like extraordinarily intense religious indoctrination. I suggest, however, that the above passage contains a clue to the real reason Collins believes in God: the spiritual longing he mentions in the last paragraph. He goes on to explain how this was reawakened in him after seeing the unshaken faith of the dying patients he treated as a physician early in his career. It was this spiritual longing — and its fulfillment in what I would call the illusion of God’s presence — that made Collins believe in God, not the frozen waterfall and certainly not any intense religious indoctrination. It came from an intuitive and unconscious source, and the nature of that source is the subject of my book.

You might argue that Francis Collins is merely one person, a single data point, possibly an outlier, and that we need more data on the correlation, or lack thereof, between indoctrination and the religiousness of elite scientists before we can accept or dismiss the role of indoctrination in their belief. I would agree, and fortunately that study has been done — not of NAS members, but of the equally prestigious and elite Royal Society of London. About 5 percent of respondents expressed strong belief in a god who answers prayer. In contrast to the study of NAS members, however, this study also asked subjects about their religious upbringing. To the authors’ surprise, there was no significant effect of degree of religious upbringing on the respondents’ belief in God.

This result does not surprise me in the least. It is what I would predict for scientists whose education and experience in empirical thinking is far in excess of what it takes to shake off the effects of religious indoctrination. That some of them are nonetheless seduced by theistic belief is compelling evidence, in my view, that there is another mechanism at work here, something distinct from indoctrination, something so emotionally overwhelming, so intuitively appealing, that it can seduce even some of the most brilliant of scientific minds. This is what Neil deGrasse Tyson meant when he said, “There’s something else going on that nobody seems to be talking about.” In my talk in Los Angeles and in my book, I argue that this mysterious “something else” is what I call the neonatal root of religion, which comes from an innate neural model of mother. Under the right conditions, that innate model spawns the illusion of God’s presence, and the intuitive feeling of knowing that comes with that experience is especially seductive to an empirically trained mind.

This hypothesis makes testable predictions about these mysterious elite scientists who believe in God. Relative to their elite scientific colleagues who do not believe in God, the elite theistic scientists should be significantly enriched in women, physicians, and other people who score relatively high on psychometric tests of empathetic caring. And relative to members of the general public who do believe in God, the elite theistic scientists should be significantly enriched in people who identify as spiritual but not religious. I won’t explain here how these predictions fall out of my hypothesis, but you can find that in my book.

You might object that, even if I’m right about the religiousness of elite scientists, what difference does it make? They’re a tiny minority of a tiny minority. Most of religion, in most people, still comes from indoctrination. I already laid out my case against indoctrination as the only source of religiousness. Here I only want to stress that whatever it is that makes elite scientists believe in God must be the most irresistible essence of whatever it is that makes people in general believe in God. Elite scientists are by far the most intellectually resistant group of people, the ones best immunized, against the seductions of religious thinking. Whatever it is that can seduce them is surely active in the general population, too, where it is likely to be one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful, of the factors that make people religious.

The Illusion of God’s Presence Does Not Explain All of Religion

In several places in your review, you object to my central hypothesis on the grounds that there are some aspects of religion it cannot explain. On the latter point I agree with you. I never claim that my hypothesis explains all of religion, and I specifically state the opposite. On page 69 I write of my hypothesis that:

It does not claim to explain all aspects of religion, nor is it equally applicable to all forms of human religion, spirituality, superstition, or ritual practices.

Your objections of this kind are therefore irrelevant. It in no way weakens my hypothesis to point out some aspect of religion it was never intended to address. As I emphasized in chapter 3, religion is a complex and multifaceted thing, and we should not expect any one idea to explain it all. In fact I go to great pains in the book to point out the things my hypothesis does not explain, and I discuss other biological or psychological mechanisms that do account for those aspects. For the most important of these I devote entire chapters (notably 6 and 7, but also parts of 8 and 10) to explaining how these other mechanisms interact with my hypothetical innate model of the mother and how my hypothesis nicely fills holes in other theories, like Lee Kirkpatrick’s attachment theory of religion (chapter 6).

Having said all that, I still have a few additional thoughts and clarifications related to your objections.

Regarding popular images of God, you write:

Wathey feels this innate vague sense of the existence of a mother being that is built in to us as human infants can be triggered in adults to create the illusion of feeling a specific presence of a god-like caregiver. Oddly enough in the major religions it is not a mother figure of course that we are told exists, but a stern, law-giving father figure, who will burn us in his hell if we don’t worship him, and in the just right manner,…something no mother would do.

Wathey feels this innate vague sense of the existence of a mother being that is built in to us as human infants can be triggered in adults to create the illusion of feeling a specific presence of a god-like caregiver. Oddly enough in the major religions it is not a mother figure of course that we are told exists, but a stern, law-giving father figure, who will burn us in his hell if we don’t worship him, and in the just right manner,…something no mother would do.

Interestingly, many people who believe in this cruel, judgmental father-God also tell us that he is infinitely loving and forgiving. Where did that come from? This blatantly incoherent, self-contradictory image of God is so widely held among the world’s believers that it cries out for a scientific explanation. I offer that explanation in my chapter 7, where I identify two distinct biological roots of religion, which I call the “social” and “neonatal” roots. The social root comprises most of the scientific theories of religion related to the evolution of human social behavior. The neonatal root comprises my hypothesis of the innate model of the mother and the illusion of God’s presence, together with Lee Kirkpatrick’s attachment theory of religion. The social and neonatal roots give rise to powerful innate forces and intuitions, and together they explain many of the great puzzles of religion, including the two-faced nature of God. I say more about the problem of malevolent gods under the subheading, Why so many nasty gods? in my chapter 10.

Regarding Buddhism, you write:

Additionally, not all religions promote the idea of a god’s presence. Buddhism does not contain the idea of a protecting watchful god-like figure, as in Wathey’s model of a mother-like presence. Their idea of transcendence is a “oneness with the universe” not the idea of some caregiver god watching over us all. So making the claim that the reason religions are around is that we feel this need for god’s presence does not apply to all religions as well. Wathey I feel, is projecting his personal experience of god’s immanence, which he was taught was correct and true by his Christianity infused culture, to apply to all humans, or to all religions when it doesn’t.

Again, I never claim it applies to all religions, but I do predict that aspects of the neonatal root will tend to creep back into religions that explicitly reject those aspects, and we see this in supposedly nontheistic Theravada Buddhism. Thus ethnographers find that rank-and-file Theravadists worship the Buddha, pray to him for help with their problems, and seek his presence in sacred icons, trees, and relics — despite the fact that it is “theologically incorrect” for them to do these things [see chapter 4 of Slone DJ (2004) Theological Incorrectness: Why Religious People Believe What They Shouldn’t. Oxford University Press: Oxford]. Also, regarding Buddhist meditation and the seeking of oneness with the universe, there may be in this practice something highly infantile and fully consonant with my hypothesis of the innate model of the mother; I speculate on this in the section What about godless religions? in my chapter 10.

Regarding some lines in my preface, you write:

I disagree completely with his characterization that the occasional and not at all universal experience of god’s presence is an illusion (rather than a delusion) and that this “illusion” explains much of religion’s appeal: the “real reason” people believe as he claims up front in the preface to the book.

“Why is religious belief special, unusual and tenacious?” Wathey’s answer assumes “something intrinsic to human nature” rather than a cultural habit: that is, the teachings of religions as I propose.

Wathey:

“The New Atheist books were rousing and delightful reading for nonbelievers, but they largely ignored the real reason that most believers believe: their personal experience of the presence of God.”

Quite the contrary, the atheist writings, Dawkins’ book especially, went straight at the real reason folks believe any religion: they were told to, and it was unquestionable to them as a child. Dawkins’ God Delusion educated and gave permission for a whole host of believers to leave their religion behind by pointing out the absurdity of what they were indoctrinated into. He may have created more nonbelievers than any other single author or New Enlightenment figure by reassuring them it is perfectly OK, in fact healthier to question the nonsense they were taught.

I thoroughly enjoyed Dawkins’s book, The God Delusion, but I was stunned to read the following in his preface:

If this book works as I intend, religious readers who open it will be atheists when they put it down. What presumptuous optimism! Of course, dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads are immune to argument, their resistance built up over years of childhood indoctrination using methods that took centuries to mature (whether by evolution or design). Among the more effective immunological devices is a dire warning to avoid even opening a book like this, which is surely a work of Satan. But I believe there are plenty of open-minded people out there: people whose childhood indoctrination was not too insidious, or for other reasons didn’t ‘take’, or whose native intelligence is strong enough to overcome it. Such free spirits should need only a little encouragement to break free of the vice of religion altogether.

If this book works as I intend, religious readers who open it will be atheists when they put it down. What presumptuous optimism! Of course, dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads are immune to argument, their resistance built up over years of childhood indoctrination using methods that took centuries to mature (whether by evolution or design). Among the more effective immunological devices is a dire warning to avoid even opening a book like this, which is surely a work of Satan. But I believe there are plenty of open-minded people out there: people whose childhood indoctrination was not too insidious, or for other reasons didn’t ‘take’, or whose native intelligence is strong enough to overcome it. Such free spirits should need only a little encouragement to break free of the vice of religion altogether.

Presumptuous optimism indeed! And in that last sentence, I can’t help wondering whether he intended “vice” (an immoral or evil habit or practice) or “vise” (any of various devices, usually having two jaws that may be brought together or separated by means of a screw, lever, or the like, used to hold an object firmly while work is being done on it). Dictionary.com tells me that “vice” is an alternate spelling for “vise”, so maybe this was a typically and intentionally clever pun on the author’s part.

But a tightly-screwed vise it is for most people who have been deeply immersed in it, who have made great sacrifices for it, and whose social connections derive from it. It is tightest of all for those who have felt God’s presence with its attendant and intuitive feeling of certainty. For them it takes more than “only a little encouragement” to break free. What stunned me about this passage was the apparent assumption that only childhood indoctrination is involved here, and that Dawkins seriously thought he could deconvert all of his religious readers.

I’m sure you’re right that he deconverted many — I’ve met a few — but we don’t know how many. We do know that Dawkins himself was surprised and disappointed that his optimistic intention was not fulfilled. In his foreword to Dan Barker’s book Godless, Dawkins writes,

It is one thing to know that these faith-heads are wrong. My mistake has been naively to think I can remove their delusion simply by talking to them in a quiet, sensible voice and laying out the evidence, clear for all to see. It isn’t as easy as that. Before we can talk to them, we must struggle to understand them; struggle to enter their seized minds and empathize. What is it really like to be so indoctrinated that you can honestly and sincerely believe obvious nonsense — believe it with every fiber of your being?

But it takes more than naiveté and lack of empathy to account for Dawkins’s presumptuous optimism. It takes a failure to grasp what religion really is, where it really comes from, and the powerful, unconscious, and largely innate emotional forces that give it its tenacity.

One of the lines in my preface that evidently stunned you to an equal degree was this one:

The New Atheist books were rousing and delightful reading for nonbelievers, but they largely ignored the real reason that most believers believe: their personal experience of the presence of God.

You ask how this can possibly be the “real reason” most believers believe when not all believers experience the illusion of God’s presence. But I insist that most believers do experience that illusion as broadly defined in my first chapter. This definition includes not only the sudden, transient, and dramatic illusion of loving mystical presence in some moment of crisis, but also a gradual and persistent feeling that the universe is somehow mindful and benevolent, that divine assistance can always be sought through prayer, or that God lives within the believer’s heart. From page 29 of chapter 1:

Many believers cannot specify a moment of sudden mystical insight or conversion in their past. Instead they describe a long history of immersion in the religious tradition of their childhood, a gradual development of their spirituality, and an intuitive sense of a benevolent or loving presence in the universe. I explore this dichotomy between sudden religious conversion and gradual spiritual growth in chapter 6. I mention it here only to suggest that the two paths may diverge from a common source.

Yes, childhood indoctrination plays a role in this, but not all religious ideas are absorbed and retained equally well by the mind of a child. The ones that are best retained are the ones that match intuitions the child has had since birth: that an amorphous, powerful, and loving savior is out there, somewhere, and that it will respond to cries for help. This is what I call the neonatal root of religion, and from it we get the big, wide streak of infantilism that runs through all religions, though not to the same degree in each. I devote all of my chapter 5 to examples of this.

Of roughly equal importance is the social root of religion, which comprises those powerful, unconscious, and largely innate emotional forces behind our moral intuitions — the foundation of our hypersocial human nature. From this we get cruel, judgmental, and punishing gods who demand costly sacrifice as proof of belief and loyalty.

We see these two dimensions, in various proportions, in all religions. But we do not see in religion a host of other strange and demonstrably false beliefs that humans fabricate. Some people believe that psychic powers are real, or that rabbits feet and horseshoes bring good luck, or that black cats and the number thirteen bring bad luck, or that the Apollo moon landings were faked, or that Elvis Presley is still alive, or that Barack Obama was born in Africa, or that extraterrestrial visitors abduct them in the night and probe their rectums with strange machines. I could extend this list ad nauseum, as I’m sure you could, too. These false beliefs are no more or less nutty than what we find in religion, but they are not religion. The content of religion is not arbitrary, as it would be if it were purely the result of indoctrination. Instead its content is shaped by the powerful innate forces in our human nature that give rise to what I call the social and neonatal dimensions of religion. Religion is about supernatural agents who are accessible through prayer and ritual; about the salvation they can bring to us in times of need, including the transcendence of death; about the different ways we must treat members of our tribe and the heathen members of other tribes that threaten us; about the sacrifices we must make to appease God and prove our loyalty; and about the special status that God bestows on our tribe as His Chosen People.

In some religions, like Sunni Islam, the social root dominates, and you could reasonably argue that the illusion of God as a loving presence isn’t the real reason most Sunnis believe in God. But these people still feel God’s presence — maybe more as a fearsome lawgiver than as a loving caregiver — and the feeling still comes more from an innate and unconscious source than from indoctrination. It’s only the veneer — the Koran, the Hadith, the minarets, and the faceless geometric patterns in mosaic tiles — that come from indoctrination and cultural heritage. And even in this austere and authoritarian sect, Allah is called “beneficent and merciful,” and the neonatal root also feeds devotion to the faith. By contrast, in Sufi Islam the neonatal root clearly dominates, and the austere cruelty of the Islamic scriptures is largely ignored. You can find examples of the infantile aspect of Sufism in my chapter 5.

On balance, considering what I know of the world’s religions, I stand by my statement that the New Atheist authors “largely ignored the real reason that most believers believe: their personal experience of the presence of God.” When I wrote this, I intended it not as a statement of established fact but as an empirically testable hypothesis. I didn’t have space in the preface to elaborate on this subtlety, but I did in the rest of the book, especially in the section “Predictions” in chapter 13. I went so far as to write a rough draft of a psychometric test (the book’s Appendix 2) that could be used to measure the differential contributions of the social and neonatal roots in various religions and to measure separately the heritability of each in a twin study. If it turns out that what I call the neonatal root is not significantly heritable, then my hypothesis — the part about the role of the innate model of mother in religion — crashes and burns. I’d be okay with that. We would have learned something and narrowed the space of viable hypotheses. I hope the experiment will be done someday. But based on other evidence I summarize throughout the book, I think it more likely that the hypothesis will stand.

The Future of an Illusion

Thus Freud entitled his book on religion, and I use his title as my final subheading because it points to what may be the essence of our various disagreements. Our different interpretations of religion make different predictions about its ultimate fate in human culture — something Freud cared about.

I give Freud credit for pointing out the infantile nature of much of religion, but his explanations of this have not held up. He saw the source of religious infantilism in the experiences of early childhood, especially in wish fulfillment and the Oedipal complex. The wish fulfillment idea was essentially untestable, but the Oedipal theory — at least as an explanation of the incest taboo — has been tested and fails miserably. The winning hypothesis was that of Edvard Westermarck, who proposed an innate mechanism that makes us averse to sex with people we grew up with during childhood. This is yet another example of a behavior, like mother-infant attachment, that is learned during a critical period and yet requires an innate foundation.

Because Freud considered religion entirely a product of learning during early childhood and likened it to a childhood neurosis, he predicted that human civilization will eventually outgrow it in a “distant, distant future.” A mere ninety years later, it’s probably still too soon to say his prediction has failed, but fail it eventually will if my interpretation of religion is correct. If I’m right, the “presumptuous optimism” of Dawkins will never be vindicated, and Freud’s “distant, distant future” devoid of religion will never come. I don’t say this because I want it to be so; I say it because my understanding of human nature, evolution, and sociobiology persuade me of it.

Your view of the future, I suspect, is more optimistic and more in line with that of Freud and Dawkins: the relentless progress of science will continue; the promises of faith and superstition will seem increasingly empty by contrast; and as rational people walk away from religious indoctrination and stop indoctrinating their children, religion will fade away to nothing.

Neither of us will live long enough to know who was right on this issue. I will only say that the future I expect need not be dismal. We can see a hint of it today in the most secular of developed nations, like Australia and the Scandinavian countries. Secularism predominates in these cultures, while religion is taken seriously only by small minorities. Even if I’m right about the innate forces that underlie religion, the twin studies tell us that religiousness is highly susceptible to environmental factors, as you have rightly emphasized. We can teach our children to think clearly, skeptically, and empirically. We can impart through example the values of tolerance, free speech, civility, and peaceful coexistence. The day may come when nowhere in the world is it a cultural norm to fan the flames of tribalism and violence with fundamentalist religion, despite the fact that religion will linger on at the fringes of society. That, I believe, is a realistic goal.

With best wishes for a peaceful and secular future,

Jack Wathey

Share this:

Jack, I enjoyed your well researched response. I am, however, unpersuaded by your examples of the visual illusions that can vary somewhat between people. Perception is a mostly top-down process of interpretation by the brain and when that interpretation is grossly different from reality, using Gregory’s definition, we call it an illusion. The individual differences in perception of a few illusions may demonstrate differences in prior knowledge, but the point remains that all people, despite slight differences in some illusions, still have them. Unlike the feeling of god’s presence, they are yet universal, in being part and parcel to the perceptual system of all human animals. The feeling of god’s presence is not part of the perceptual system, not experienced by all people, and shouldn’t be termed an illusion. The feeling of the presence of god is not universal like all illusions, malleable or not and in fact is experienced by only a subset of humans. Even the devout may never feel god being there. For these reasons, to use the term illusion is yet incorrect.

In addition, even the small subset of malleable illusions, are still experienced. They do not go away, merely by thinking them through. Once again, they are not cognitively penetrable, wholly unlike the delusion of god’s presence, which is readily discarded by many, once they realize they were merely experiencing their own thoughts, hearing voices in their heads, or interpreting their feelings which they were told was some god. Not an illusion, but an instructed, cognitively penetrable, and thereby discard-able delusion. Illusions are not discardable. I feel this is a minor point and does not take away from the power of your book. In the following, I tried to comment on most of your additional commentary. It really got me thinking. Thanks for taking such time and effort to respond to my analysis.

As you point out the Leuba experiment, given its small sample size and poor controls is an inappropriate example for demonstrating people’s sense of the presence of god. Blind people, for example become very attuned to space perception between themselves and another person or object, using sensory cues most of the sighted are not attuned to. Whatever may be claimed by this experiment is highly suspect. It doesn’t add to your argument.

The rubber hand illusion requires conflicting visual/tactile input to alter the perceptual interpretation of the location of bodily sensation. The illusion is achieved through conflicting sensations, not persuasion, not thought, not indoctrination, unlike the god delusion. I don’t think this example helps justify use of the term illusion. In fact, it demonstrates an illusion as being a gross misinterpretation of reality by the perceptual system. This is not a delusion, which is a false belief. One’s feeling of where the tactile stimulation is occurring suddenly flips into the lifeless rubber hand after a minute or so of contradictory input into the brain. What I find so fascinating about the rubber hand illusion is that it makes such a damning example negating the absurd claims of some philosophers that consciousness, specifically qualia, must somehow be something more than the matter and processes of the physical brain.

I didn’t say religion was solely a product of culture and learning, I said the delusion of god’s presence for most people was, and must be taught. We do have biological tendencies as evidenced in the identical twin studies to religiosity. But again, as in most identical twin’s studies with various traits, the genetic component is on the order of half of the variance. Much of what is actually expressed as religion is learned. Schizophrenics can interpret their auditory hallucination as voices in their heads from a religious figure, not all who have them do, but when they do they reflect the religion of their culture. They hear the gods they know of, the delusion of a god’s presence is culturally driven in that case as well, despite the strong genetic component making them susceptible to voices in their heads.

I like your use of the data highlighted by Neil DeGrasse Tyson: that 7 percent of elite scientists still believe in god. It is a great question, one to be followed up on as he rightly points out. I’ve not read anyone has, I may have missed it. It would be fascinating. One question might be: “Did any of them come to this belief without any cultural learning?” Did they grow up atheist, non-theist, or never heard of a god or any gods in their surrounding culture, ever, and then one day come to the conclusion that there must be a god, all by their lonesome, with no cultural influence? I suspect the answer might be zero. Also, what is the nature of their god belief? If pressed, would they end up with a nebulous sort of Spinozan god as Einstein and other scientists tend to? Furthermore, social pressure to conform is quite powerful and unconscious. Do these few still believe for the various social reasons that make it hard to let go? There are a lot of reasons one could explore besides the delusion of god’s presence being the reason they yet believe in some way. I don’t think this data can be assumed to exclude social and cultural influence in any way.

Francis Collins’ longing for meaning and purpose, our innate sense of awe, became channeled into devout Xianity. He came to believe Jesus exists and the Bible stories are true, despite as you quote him he previously became convinced that many religious faiths held no foundational truth. The overwhelmingly dominant religion of his culture became his delusion. When pressed by Bill Maher in Religulous, Francis seemed unaware of the most basic of Biblical scholarship knowledge about his own faith, such as the Gospels being written anonymously. His subsequent attempts to convince his fellow Xians to take a scientific approach to their faith thru his BioLogos website, though admirable, were met with pushback from the Conservative Xians. For example, he tried to get them to take the genetic data seriously that dispels any possibility to the Adam and Eve myth. He readily discarded that delusion, but clung to his own delusion that much of Jesus’s deeds and saying were yet true. A little bit of that same scientific analysis he used daily for an entire career in his genetics work, applied to the well-established and published Biblical scholarship, would most likely diminish his estimate of the probability of any of Xianity being true. But being a human, as well as a scientist, I suspect he never did. He possibly avoids that analysis of his own faith, it is not at all uncommon, even among the educated.

So, Francis is an example of another very bright man, fully immersed in science who can’t let go of his own delusions, ignoring the very logic of evidence based reasoning that he admonishes his fellow Xians to use. Humans are good at compartmentalizing to avoid their own cognitive dissonance, which is another reason religious delusions persist, even in very bright, educated people. Whether the motivation can be explained by sense of awe, needing to be in control, needing to feel right, comfort in a faith community, or having a predisposition for a god’s presence is yet to be determined. I suspect these and other reasons could be discerned, and the feeling of god’s presence may be but one of many, not at all the real reason people believe. Any of the above reasons I mentioned in the previous paragraphs may well explain the 7%’s remaining belief.

As far as the Royal Society study, the above reasons may also apply why the 5% still maintain a delusion that there is a god that answers prayers, when there is no evidence for, and mountains of evidence against the claim. Despite being highly trained elite scientists, they are humans. They may be unparalleled experts in their field but schmucks in other ways of thinking and knowing. (I have known many, you too, I suspect). The lack of effect of religious upbringing does not take into account a number of factors: social pressure, cultural immersion, avoiding cognitive dissonance, a feeling of comfort that believing in prayer brings, etc., etc. There are whole host of reasons that may come into play. I disagree with your statement that for these 5% that “… education and experience in empirical thinking is far in excess of what it takes to shake off the effects of religious indoctrination.” For most yes, it works, but not all. For Francis and these 5%, and the 7%, they may not have taken the logic all that far, for but one more explanation. To consider any of this as support for your “illusion of god’s presence” is a bit of a stretch at this point.

For but another example, Ken Miller, the biologist, author, and Creationism fighter I greatly admire, claims to be a devout Catholic. He decries and dismantles the abject delusional thinking of Creationism and Intelligent Design, yet as a Catholic and Xian he must adhere to the myths of human parthenogenesis and transubstantiation, along with the idea that Mary didn’t die but ascended directly into heaven (she had to, as she couldn’t die, not being born with original sin, which she just couldn’t have had because she bore the also-sinless son of god!). For a brilliant a guy as Ken, being a Catholic, much less a devout one, these are non-negotiables. Yet as Lawrence Krauss reported, when he discussed these ideas with Ken at a conference; “How could you as an eminent biologist buy into the virgin birth, or the changing of water into wine and the wafer into flesh?” ……and other silly doctrines that define Xiansanity/Catholicism, Miller backed off into the “maybe it’s just a metaphor” defense, believing in not the actual reality of such occurrences but their “spiritual” reality. When pressed to apply his empirical reasoning to his faith claims, they faded away into lame excuses. Some never get cornered like that, and many don’t do it to themselves.

So, as I said I disagree with your claim that really, smart, scientists should have thrown off such delusional thinking by their immersion in science and empirical thinking. It happens all too often with so many of the faithful, scientists or the nonscientist public, in that they do not think their faith through. People often do not turn that spotlight on their own misconceptions, even when they are experts at wielding the logico-empirical scalpel in other areas. And their motivations may be many, beyond the feeling of the presence of some god. I suspect many of reasons will have a strong social and cultural component. Ken Miller and Francis Collins and that 7% and 5% are in the minority to be sure, but they are complex human beings, not one-dimensional rationalists. It can take a long time for some to reconcile their absurd beliefs with their otherwise rational ideas. If Ken Miller had never been taught that Catholicism was the “real deal”; wanna bet he ever would buy such nonsense? The personal emotional toll in discarding beliefs can be as huge as the social ones. Those I suspect are some of the underlying reason so many cling to absurd beliefs, not the feeling of the presence of some god.

I share Dawkins optimism still. Information Kills Religion. For most, if not all, eventually. Just not right away as he found out, and as he expressed in Barker’s introduction as you point out. It takes time and often not just mild explanation. Attack of the ideas (not the person) is often what is needed. Militant atheism works, and by militant, I mean handing someone a copy of the ugly passages in their scripture or giving them a copy of one of Bart Ehrman’s books, or Dawkins or Hitchens’. Sarah Haider of Ex-Muslims of North America points out is was a “militant atheist” who repeatedly challenged her Islamic faith by giving her copies of the nastier verses of the Koran. Like many a Xian, she denied they were in there, he must be fabricating these atrocities, and she boned up on her knowledge of the Koran and hadith to blow him away, once and for all. A month later in discovering all he showed her was true and discovering a lot more for herself and bingo…she was no longer a Muslim. It doesn’t happen that quickly for many, but may take years, even a decade or more as with Dan Barker. Books like Dawkins and Hitchens and all the others do attack the main issues: child indoctrination, cultural pressure to conform, and the knowledge that religious claims are nonsense, sometimes cruel nonsense.

I just love this quote from Tom Paine:

“Some people can be reasoned into sense, and others must be shocked into it. Say a bold thing that will stagger them, and they will begin to think “ Thomas Paine

In addition to challenging unquestioned faith claims, the fact that it is “OK not to believe” may be the most powerful message of Dawkins and everyone’s else writings. Knowing there are others like you, you are not alone, there is another community to replace the faith one you have left behind is huge. Being social animals, I think those reasons all far outweigh the uncommon experience of a god’s presence. Leaving your faith community behind is really hard and you need another one to join: finding out that it’s OK, normal and there are a whole community of people nearby and worldwide that have made that leap already is liberating for so many. That is the most common response Dawkins gets in his Convert’s Corner emails. He and Hitchens, Harris, Krauss, and so many others have received such responses by the thousands, which represent just the tip of the iceberg. I’m small potatoes compared to those guys, yet already in my local Chi Metro talks, I’ve gotten the same grateful response from folks that talk to me afterwards. They hear info they have never heard and realize it’s OK to question and leave your faith, and that so many others have already done so. It is still not OK in the wider culture to drop or criticize religion. It still holds a stranglehold on even our modern culture, altho we are loosening its grip tremendously of late.

Another step that is hard to take is to reconcile the dissonance that you have been sold a bill of goods, you have been duped. It is hard to realize you were hosed, that it is all nonsense. Then you need to reconcile the fact that those that taught you: your minister, parents, community, teachers, that they didn’t mean it, they didn’t intentionally tell you what they knew were lies, they sincerely believed it too. There is so much more involved, to discarding belief, that is orthogonal to any feeling of god’s presence.

If Dawkins play on words as you describe with “vice/vise” meanings was his intent, he is right on both counts. Child indoctrination is disgusting. Cognitively immature and emotionally vulnerable adolescents, searching for identity are easily converted. Barker, Ehrman, Andrews…go down the list: so many “born again” at age 15 or so. Kids pulled into the madrassa, Bible study, the temple all over the world. And when nearly everyone in your family, town, culture believes in some way it is very difficult to say no and think for yourself. Many adults never come out for fear of rocking the boat. The social pressure to conform, both overt and unconscious is enormous. Western Muslim kids raised in moderate Islam, suddenly going hardcore, adopting the hijab and running off to join ISIS is not a mystery at all. Islam sells a pre-packaged identity every bit as seductive as being born again, and as coercive as any hard-core Xian or Orthodox Jewish sect.

I think Freud is so full of shit in so many ways I won’t even comment on his ideas of religion. I disagree that religion can’t be discarded but not for agreement with Freud’s childhood neurosis ideas or any of his other imaginative musings.

I think religion as we know it today, can be discarded for the delusional myth-promoting, moralizing, bad habit that it is. It won’t happen in my lifetime, but the trend since the Renaissance and Enlightenment has been down. We are incomparably less religious, at least in much of the West, than the average person living in the 1500’s, even 1800’s. Superstition and fear of god’s retribution was the norm, in response to disease and natural disasters. Also, religions weren’t like Islam and Xiansanity, in Neolithic or Classical times. The moralizing, and stern creator god components were not part of primitive early religions. The patriarchal, moralistic, divisive institutions we see today are a historical accident, one we can discard thru education. End child indoctrination and religions disappear one by one. No-one believes in Zeus or Osiris anymore of the ancient Greek and Egyptian religions, precisely because no-one teaches them to children as truth anymore. The Hebrew and Arabic mythologies would die off just as quickly if we stopped teaching them, and coercing their membership thru social pressure.

We are seeing it in the rise of the Nones in the US, following the secular advance of the other developed nations around the globe. This New Enlightenment movement is but a bit over a decade old now, since the publication of Sam Harris’ “End of Faith” in 2004 kicked it off. All the “New Atheist” books that followed, and the meetups, the rise of the Nones, the growth in secular organizations, the daily attack on religious ideas in all media, the Reason Rally, all the meetings we attend, the plethora of podcasts and secular videos, the dozen comics that regularly wail on religion…all of this was not happening except on the very fringe of society in the 60’s thru the 90’s. Now it is mainstream. Give it a few more decades, or a century of the exposure of the ridiculous claims of religious mythologies, their utter lack of evidence, their divisiveness, and often cruel and repressive tendencies, and we shall see if most people will no longer be bamboozled by the abject delusions of religion. Modern religions have had a 2,000 year headstart. Give the secular attack on religious mythology some more time and see what happens. It is very early in the game. Religions are not natural, needed, nor necessary. That are not an immovable part of human nature. Over 2 billion irreligious folks on the planet and more coming out very day and many more hidden in cultures where they dare not make themselves known, do not support the hypothesis that religion is natural, and a necessity and can’t go away. Too many have learned to live utterly without it.

Whatever biological predispositions we have: a sense of awe, belonging, feeling of transcendence, social conformity, etc., like our sense of agency, can all be fulfilled without religion. The delusion of god’s presence must be taught to explain those longings. And it isn’t true, there is no god present, it is a false belief.

Our brains for example may predispose us to agency as children, but without religious indoctrination, we outgrow the delusion of ascribing a person-like cause to natural phenomena. Religion is not an inevitability of bigger brains. Too many of us modern humans don’t buy into it, or easily discard it. Without cultural sanction and transmission, it dies a quick death.

You do claim in your preface that the feeling of god’s presence is the “real reason” people believe. I’m glad you qualified that on page 69 that it doesn’t explain all religions or religiosity. But I still disagree it is the real reason. The feeling of god’s presence is at best a minor reason, one of many, and not experienced by most humans, even most of the devout.

My bringing up Buddhism is to attack your use of the term illusion, not that the feeling of god’s presence explains all religions. Illusions are universal, the feeling of a god’s presence is not part of Buddhism, and not universal. The Buddhist religion is a syncretic mess of local religions, with devotional practices to all sorts of minor gods and bodhisattvas out in celestial realms. It is no wonder some worship the Buddha even when it is considered doctrinally incorrect. Minor god worship, prayer and devotional offerings are widespread throughout Buddhist practice. They were taught those practices and they are huge in their wider culture.

Cruel, judgmental gods don’t act like loving mothers. I would contend that peculiarity of the Abrahamic religions of patriarchal stern gods, is again more culturally driven than derived from any innate biological longing. Those religions have become so dominant worldwide that we tend to think of religion thru their lens. It is mere historical accident through conquest that the 2 main Abrahamic religions derived from the same stern patriarchal culture (Islam is but an extension of Judeo-Xian thought) dominate our modern world.

Delusion is overwhelmingly not associated with pathology. For but one example, over 40% of Americans have believed the obviously delusional idea of Creationism for many decades now. Only a very small percentage of those same people may be suffering from some mental disorder, which if so, is unrelated to their Creation belief. They don’t suffer from an illusion of Creationism, but a religiously motivated delusion, as is the case with the feeling of god’s presence. The claim to avoid using delusion as it is associated with pathology doesn’t hold up. I don’t think Ken Miller and Francis Collins or the 7% and 5% are suffering from pathology at all. They were sold a pack of nonsense from their culture, whether thru direct religious instruction or not, and despite their formidable reasoning skills, are normal humans like anyone else and a small percentage of us (Mormons, who are otherwise worldly realists for the most part) believe just batshit crazy ideas. Those ideas are hard to let go of for some, but these delusions are cognitively penetrable, discardable and not illusory.

Once again, I thoroughly enjoy this exchange. Teaching at community colleges I don’t get a lot of interaction with colleagues on intellectual topics. I do get a lot of stimulating discussion with all the secular meetups I attend and the talks I give locally. So, I do appreciate your corresponding with me whether we agree on some things or not. Maybe if my book marketing attempts over the next year are somewhat successful and I get a chance to speak at regional or national meetings, we will get a chance to meet someday. In the meantime, take care and thanks for being a part of the secular advance.

Many thanks, William. I too enjoyed this exchange and feel that it clarified my thoughts on some important points. I won’t try to give a point-by-point rebuttal to your reply. I’ve already made my case as best I could in the original post, in the book, and in my talk in Los Angeles. I think we’ll just have to agree to disagree on some things. But on the most important things we agree, and I’m delighted to count you among my secular friends. And yes, I hope to meet you in person someday!

Jack, My sentiments exactly. I hope the book is doing well and Ill be at Gateway To Reason in St Louis in July and the Mythicist Milaukee Conference in Sept, selling my book and promoting the Secular Coalition for America. I will attend the FRFF annual convention in Madison in Sept as well in case you will be going to any of those meetings. I plan to be doing a lot of local student group and meetup talks in the Chi area all fall and hope to build enuf notoriety and exposure to get invited to speak at regional or national meetings down the road, where we may bump into one another. Thats the plan anyway. Enjoyed our exchange very much!!

maybe see you soon

take care

bill

Great exchange of ideas, and an excellent book, although I tend to side with Dr. Wathey, based on my own personal experiences and countless interviews I’ve conducted. There’s something more to this than just conditioning. As an example, I don’t think the following personal incidents can be explained by learning alone considering that they were never strongly reinforced as a child and completely extinguished for years because I no longer, intellectually, believe in the supernatural, but, I just can’t seem to let go of them: “Most recently, I was in a desperate situation creating deep anxiety and fear, and I made a promise that I would start believing in him if he would save me from this predicament, very odd. Another incident was when I was stranded in the San Pedro Parks Wilderness at 11,000 feet in New Mexico with my seven year old daughter, dehydrated from altitude sickness and lost, out of desperation, I call out to God to help with no strings attached.” Dr. Wathey, do you think these reactions fit within your model? Also, a recurring theme for me, why would I promise to believe in him, perhaps out of guilt or fear? And, on a different note, will you be able to empirically illuminate the mechanisms behind your model in your sequel? It seems hard to be able to ever replicate or induce a fearful state in the lab and then record the pathways in a fMRI. So, as some have said, much to my dislike because I find your model promising, that this model at this time is nothing more than speculation akin to a lot of things in evolutionary psychology. I appreciate any thoughts you may have on my comments. Thank you.

Jon,

Many thanks for your comment and personal anecdotes. Yes, prayers of desperation of the kind you describe fit extremely well with my hypothesis. You note that for years you have not intellectually believed in the supernatural, yet when in these situations of desperate helplessness, you have spontaneously prayed to God and even tried to strike a bargain with him to win his divine intervention in the crisis of the moment. Why would anyone pray to a God they don’t believe exists? My answer is that your intellectual disbelief in the supernatural can momentarily lose out to a powerful, emotional, and intuitive longing for salvation in the face of helplessness. This longing comes from a different part of the brain than that which supports your intellectual skepticism about the supernatural, and it leads to decisions or reactions that are fast and effortless. This fast, intuitive kind of thinking is what Daniel Kahneman calls “system one.” By contrast, the analytical reasoning behind atheism — what Kahneman calls “system two” is slow and takes much effort. Intuitions can be innate or learned, but I argue that the intuitions behind religion are largely innate and come from two selective pressures in our evolutionary history. These are the pressures for adult human social behavior and for the survival of helpless human infants; they give rise to what I call the social and neonatal roots of religion, respectively.

You ask about empirical evidence for my hypothesis and worry that it “is nothing more than speculation akin to a lot of things in evolutionary psychology.” I understand that concern and I applaud your demand for empirical evidence. Of course I’ve tried to show in The Illusion of God’s Presence that there is a great deal of empirical evidence that supports the hypothesis, including evidence for the existence of these two distinct roots of religion, for the importance of infantilism in religious imagery, and for the existence in human newborns of an innate model of mother and an expectation of her existence. I’ve also offered a list of empirically testable predictions in chapter 13. You might want to take another look at that section (pp 261-3).

More specifically, you ask about neural mechanisms and my forthcoming sequel. You’re right that it’s difficult to study something as elusive as the feeling of God’s presence using fMRI, but some intriguing experiments have been done along these lines. The short answer is that, in the sequel, I do speculate on what anatomical parts of the brain are likely to be involved in mystical experiences of this kind, and I have an entire chapter on empirically testable predictions at the level of neural mechanisms. I discuss a little of this in my lecture at the Center for Inquiry in Los Angeles.